When we get together in our CAC meetings, we often find ourselves reflecting on the learning we did at PRI — those moments in workshops and intensives that stay with us. We thought it might be helpful to share some of those reminders here, as a way of reconnecting with tools that many of us still lean on.

One of the most memorable frameworks for many of us was Virginia Satir’s Five Coping Stances. Do you remember where you found yourself in those early sessions, doing that hard work?

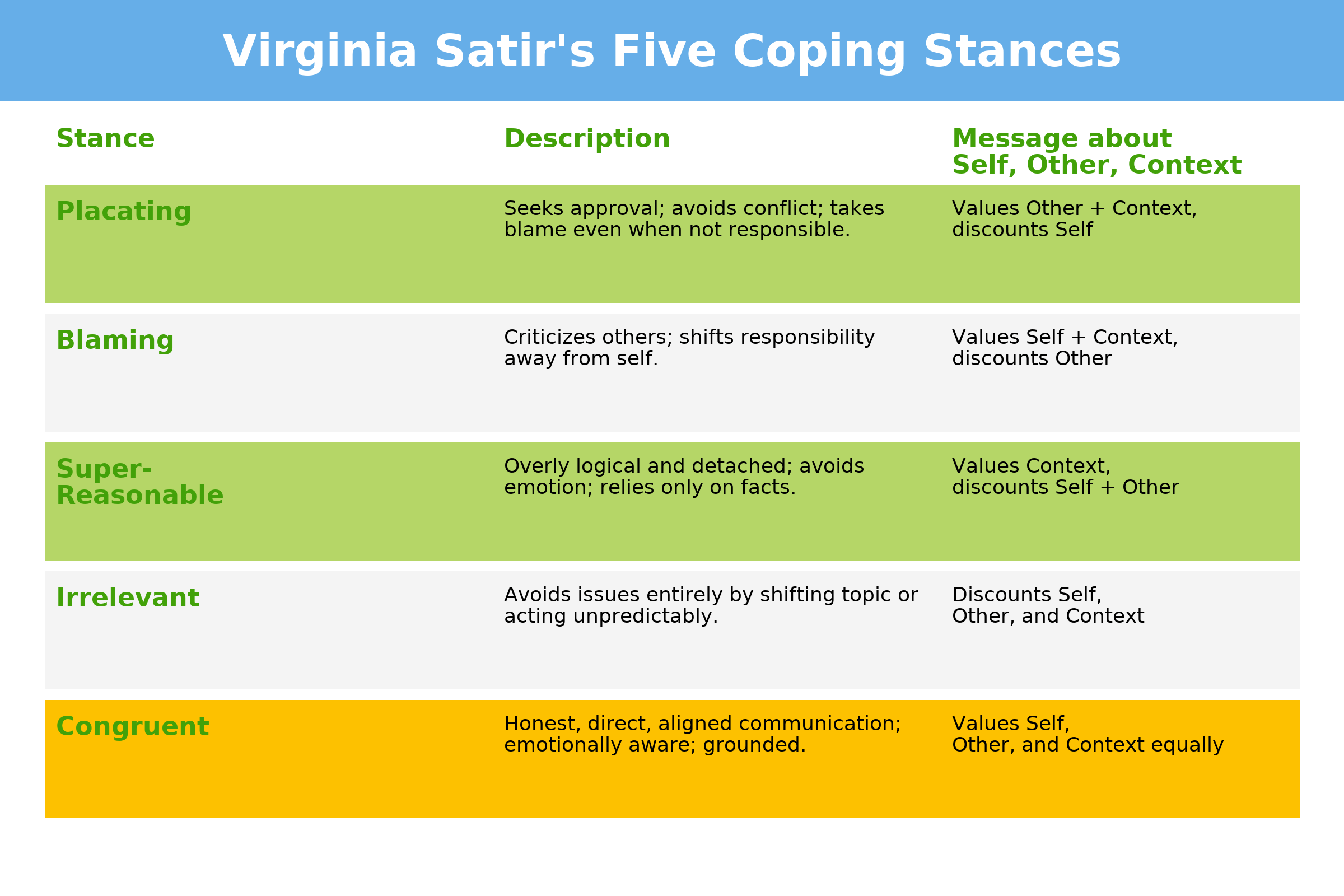

Satir’s family therapy model describes five communication or “coping” stances people often adopt unconsciously under stress: Placating, Blaming, Super-Reasonable (or Computing), Irrelevant (or Distracting), and the ideal stance, Congruent (or Leveling).

These stances help describe how we behave and communicate when things feel overwhelming. According to Satir, they aren’t conscious choices — they’re survival patterns many of us developed early on to navigate conflict or protect ourselves in stressful environments.

“Virginia taught that our coping stances are closely tied to how we see and value ourselves,” said Dr. Victoria Creighton, Pine River’s Director of Clinical Training and Family Services, in reminder.

“When we feel grounded and connected to who we are, we’re more able to show up in a balanced, congruent way. But when we lose that connection — often because of old patterns we learned in our families — we slip back into other stances just to get by. Understanding this helps us recognize what’s really going on underneath our reactions and gives us a path back to ourselves.”

The goal, of course, is to move toward Congruence: a grounded, healthy response where we’re able to balance awareness of ourselves, others, and the situation. Easier said than done sometimes — but worth striving for.

Coping Stances in Parenting

When we think about these stances in the context of parenting, they’re not “parenting styles” but stress responses — the default ways we communicate when emotions run high.

- A placating parent may give in to avoid conflict or try to keep the peace, even when boundaries are needed.

- A blaming parent might over-focus on fault or responsibility and direct frustration toward the child.

- A super-reasonable parent may rely on logic, facts, or lectures while unintentionally sidelining their own emotions or their child’s.

- An irrelevant parent might deflect with humour or distraction to avoid harder conversations.

- A congruent parent—the goal—communicates openly and honestly, acknowledging their own feelings, the child’s feelings, and the reality of the situation.

These ideas don’t just apply to parenting, of course. Many of us have noticed these patterns in how we communicate with partners, colleagues, friends — even ourselves. That slow, steady work of moving toward Congruence continues long after our time at PRI, and we hope this refresher is a helpful reminder of that shared journey.